Muses & Musings with Choreographer Warren Carlyle

In my role as Columns Editor for SDC Journal, I interviewed choreographer Warren Carlyle for the Muses & Musings column, which highlights directors and choreographers sharing their current sources of inspiration. This was published in the Fall 2025 issue of the magazine.

Who or what inspired your career in theatre?

I grew up in a village in England, and the village didn't actually have its own theatre. So a lot of my early inspiration came from MGM movie musicals. Anything that Fred Astaire did, anything that Gene Kelly did—that was really my first access to dance of any kind.

I studied in the local dance school, and I graduated from there into full-time ballet school, just outside of London. Classical ballet was the bedrock of my training. Then I danced. I worked on 10 West End shows before I came to America. I danced lots of different styles, in lots of different productions. I was a swing, a dance captain, an assistant choreographer, and a resident director. I found an interesting path and I think those early MGM movie musicals led me to what I'm doing now. Big, bright, joyous shows. That's my hope.

Where do you get your inspiration now? Is it books, music, visual art?

One of my earliest memories is listening to music and imagining things. I think I just always had that thing—I hear music, and I see people moving. Now I sit in my apartment and listen to music and imagine people dancing.

I spend a lot of time in my scripts and in my music. I always have a dance arranger. I always have a drummer. I do research, but I try not to be bound by it or biased by it. Especially with some of the period things. Pirates!, as an example of that, is set in 1890. And if I was bound by period, I'd really be in trouble, I think; I don't know quite how I'd make that dance in the way that I have.

As we speak, your production of Pirates! A Penzance Musical, a reimagining of Gilbert and Sullivan's The Pirates of Penzance, has just opened on Broadway. Tell us about the world you created for that show, and what inspired it.

Pirates! is very much a kind of decoupage world. I wanted the dance to feel like that. The clothes—beautifully designed by Linda Sherwin—feel like that; the scenery—by David Rockwell, lit by Don Holder—feels like that. I wanted the choreography to be in the same world as the scenery and the costumes.

One of the biggest opportunities with Pirates! was to make something that's traditionally a Gilbert and Sullivan operetta—something that's not a dance—to make it dance. To make it move, give it style, give it a language all its own, to make it for this particular generation. We've updated it already, because we've set it in New Orleans. That gave us license to change the music. Then as soon as we got jazz and Creole influences in the music, that started to influence the casting, and that started to influence the way people are moving.

There are very distinct character groups in Pirates! That was fun for me. There are the pirates, the daughters, the police, and these very well-defined principal roles: the modern Major-General, played by David Hyde Pierce, and the Pirate King, played by Ramin Karimloo. How's the Pirate King going to move? How is he expressing his physicality and his strength? Jinkx Monsoon plays Ruth, the nursemaid. How does Ruth move? How does she express herself?

I researched British Naval semaphore [flag signalling] for Pirates! I wanted to create a language for the modern Major-General, and I wanted it to be historically correct. The flags in Pirates! are actually correct: blue and white was correct for the land, and orange and red is correct for "at sea."

So for me, it was a massive opportunity to really create a world for each character and group, and then to push all those things together. Pirates! is this beautiful combo of a show with very distinct movement styles for each of these groups, and then for each of those principal characters.

The other thing I wanted to do is to have fun. I wanted to make a bright, joyous, intelligent, humorous piece of theatre. I didn't want it to be too thoughtful, choreographically. I wanted it to move. I wanted it to move beautifully—every time it stopped, I wanted it to look beautiful—but I wanted it to move.

Where do you find inspiration outside of your work as a choreographer?

A friend of mine, David Rockwell, who's a brilliant designer, has really encouraged me to paint. I really haven't painted in my life. I don't remember ever having painted in watercolor, certainly. I really like it. I feel like I paint pictures with people for a living. That's really what I do.

I hope I paint beautiful pictures with people and tell beautiful stories with people. And now I've started to try that with paint, just gently with a brush, and see how that works. It's really humbling and really challenging, but I like it. My brain likes it.

You paint lot of landscapes, so you're painting with people in your choreographic work but not yet in your visual art.

It's tricky. People are way too hard for me. Unless I'm struck by something at New York City Ballet. Quite often, those shapes really inspire me. I love going to ballet, and City Ballet has been such a big place of inspiration for me over my 25 years in New York. I continue to go to City Ballet every season, and I continue to be a huge fan of those dances, and of that organization too. That's a wonderful artistic venture, and something that I'm constantly inspired by.

I also love seeing other choreographers' work. I'm fascinated by it. I'm such a huge fan of this strange and wonderful group of people. I'm always curious about what makes someone tick. Why is that rhythm like that? Why are they traveling like that? Why did they choose that step? Why is that that color? Why does that go across the phrase, and why did they line it up the end of the phrase? The way people use music is fascinating to me, too. All of us are wildly different. I'm a massive fan of the theatre, massive fan of directors and choreographers.

Warren Carlyle is a Tony Award-winning director and choreographer. Broadway: Pirates! The Penzance Musical; Harmony; The Music Man; Yes We Can; Katie; Hello, Dolly!; She Loves Me; On the 20th Century; After Midnight; Hugh Jackman: Back on Broadway; Chaplin; A Christmas Story; The Mystery of Edwin Drood; Finian's Rainbow; and A Tale of Two Cities.

Innovations with Kristin Hanggi + Maxx Reed

In my role as Columns Editor for SDC Journal, I wroked with contributor Ellie Handel to edit this interview for the Innovations column, which highlights directors and choreographers working on the leading edge of production, process, and technology. This was published in the Fall 2025 issue of the magazine.

The new musical It's All Your Fault, Tyler Price! premiered at the Hudson Theatre in Los Angeles in November 2024. The show focuses on the family of a student with epilepsy, a brain disorder that causes recurring seizures. About three percent of people with epilepsy suffer from a condition known as photosensitive epilepsy, in which exposure to flashing lights, strobe effects, and other intense visual stimuli can trigger seizure, migraines, or dizziness. SDC Journal contributor Edie Handel spoke with director Kristin Hanggi and choreographer Maxx Reed about their journey to understand how some theatrical lighting design affects individuals with photosensitive epilepsy and how the creative team worked to make Tyler Price safe for all audience members to enjoy.

Kristin, how did It's All Your Fault, Tyler Price! come to be, and how did you get involved?

KRISTIN HANGGI | Back in 2007, a producer gave me a CD and said, "See if you think this could be a musical." It was an album written for children that Ben [Decter, It's All Your Fault, Tyler Price! composer, lyricist, and co-book writer] was one of the co-composers on. We met for dinner, and he told me the story of his family and how his daughter was diagnosed at 17 months old with catastrophic childhood epilepsy. Because Ben is a composer, he dealt with it by writing songs. He started playing me songs he wrote to try to find his way through. From 2007 to 2019, Ben and I just tried to figure out how to tell this story. We started working with the Epilepsy Foundation of America, the Epilepsy Foundation of America in Los Angeles, and the Children's Ranch.

During this time, as we started getting our resources in line, I participated in Broadway Dreams [a non-profit theatre performance program for young people that creates inclusive spaces where students of all backgrounds can explore their artistic potential]. One of the choreographers I worked with was Maxx Reed. I watched Maxx start doing this choreography with these young people and I just said, "Well, who's this genius? Where has he been my whole life? Whoa." We got into a taxicab, and he started to talk a bit about himself. I learned that his niece has epilepsy and that he started a foundation with her called EpiArts Alliance.

What is EpiArts Alliance, and how was it established?

MAXX REED | My niece, Anzii McNew, her goal is to be a Broadway performer. When she was diagnosed with epilepsy, she got knocked back a little bit. I started bringing her to Broadway Dreams with me as a student. I discovered a lot about how to be sensitive to her as a performer and what was needed to protect her from having seizures on stage. I was trying to communicate that to other teachers, choreographers, and directors that I work with in the Broadway Dreams ecosystem.

Anzii and her mother, Heather McNew, became the creators of EpiArts Alliance. [Founded in 2023, EpiArts Alliance supports performers with epilepsy and photosensitivity through education and awareness campaigns.]

KRISTIN | Maxx and EpiArts brought a very important component to Tyler Price because I had not been educated, up to that point, about how to create a theatrical environment that was sensitive to the needs of audience members with epilepsy.

I learned Maxx's niece gets triggered by certain lighting cues. When Maxx was performing in Beetlejuice, he would have to tell her when certain cues were coming. Then she knew that if she put a palm over an eyeball, she could watch it without it triggering a seizure. Here it come, Kristin—who directed Rock of Ages, which is all flashing lights all the time—and I didn't know that, I thought only strobe lights could trigger seizures. That's not true. It's not just flashing lights, it has to do with color spectrum as well. If someone has epilepsy, light sensitive epilepsy, it really is an interesting health matter for them.

Before Tyler Price premiered, Kristin and Ben Decter participated in a lighting safety research roundtable organized by EpiArts and inspired by some of the work Maxx was doing with Anzii for Broadway Dreams. The discussion was attended by photosensitive researchers Dr. Arnold Wilkins and Dr. Laura South, lighting designers Donald Holder and Barbara Samuels, and ConsultAbility founder Paul Benhosrt. How did this conversation affect your team's work on Tyler Price's design?

MAXX | We were lucky enough to get wonderful directors, lighting designers, and doctors—literally the man who wrote the book on photosensitive epilepsy—into one giant Zoom call. Now there's a strong relationship between doctors who really understand the science of epilepsy and lighting designers who understand the science of their craft.

We started coming up with protocols for photosensitive design. Strobes and flashes are often unavoidable in theatrical storytelling; however, there are ways to design so that the risk is minimized. For example, designers can point the strobes toward set pieces rather than towards the audience and can change the frequency and color contrast to minimize risk for photosensitive audiences.

Tyler Price was very much a case study. Because we had heard from researchers early on, we approached this production with empathetic design from the start.

KRISTIN | Jamie Roderick [Tyler Price's lighting designer] talked to EpiArts to get all that information and research. Jamie created the show to be light sensitive and it still had gorgeous lighting cues.

MAXX | Jamie's work was insane. It was gorgeous and it was safe for all audience members. Jamie and the team made sure to include detailed signs in the theatres of the exact flashing light cues and scenes. They went beyond the "Flashing Light Warning" sign that is standard practice in theatre. That's a core mission of EpiArts, to provide audiences access to understand the potential risk ahead of attending a show.

This process of empathetic design and implementing safer lighting practices with Tyler Price proved that it can be done, and you still have all of the storytelling pieces there. My niece came and watched the show three times. One of those times she sat in what could be potentially the most triggering seat in line with a particular light. To watch my sister sit next to my niece and never have to shield Anzii from any cues...they could both watch the show. It just shows that it's possible.

KRISTIN | We also had a sensory sensitive performance where we also looked at the other elements—sound, conversation with the audience—those kind of things. While photosensitivity is often focused specifically on light and visual triggers, we took a holistic approach that considered the full sensory landscape of the production. For that performance, we lowered the overall volume, softened sudden sound cues, and worked with the cast on respecting there were no jarring vocal spikes that might be jarring. We also communicated clearly with the audience about what to expect and made space for movement and vocalization during the performance. Our goal was to preserve the emotional integrity of the show while adjusting the delivery to be more accessible.

Has your work with EpiArts and Tyler Price shifted how you approach your craft?

KRISTIN | An undercurrent that developed in the show was being willing to talk about things that are challenging, even if we don't have language for them yet. The creative team learned how to do that together, asking each other, "What do I need in order to feel safe in this space? Can we make an inclusive space for each other?" When it was okay to ask for our needs to be met, we discovered that we could create a process that felt good to all of us, but we have to learn how to talk about our needs first, even if we don't know how to name them.

The process has become so important to me. I want to make sure that it's nurturing for myself and my collaborators, the team, to create something sustainable. It has to feel good in my body. That has profoundly shifted for me. The work is integrated with a deep internal listening.

MAXX | It has changed the way I choose projects. I decided to go and be a part of this show so that I could make something my niece would be proud of. It's made my filter for the things I want to do with my time much finer. I now know that it's possible to keep creating while making sure that the work aligns with things I would like to teach, experience, or grow in, and I get to be beside people that I can learn from, love, and respect.

It has changed the way I interact with people in the room. It has changed—from a technical standpoint—what I think is necessary in order to make something interesting. Some of the most effective things in this show were the simplest. I'm going to trust that more for the rest of my career.

Kristin Hanggi is best known for directing the smash hit Rock of Ages, for which she received a Tony nomination for Best Direction of a Musical. Other directing credits include the original productions of the pop opera Bare (Hudson Theatre); Accidentally Brave (Off-Broadway); Clueless (The New Group); and Romy and Michele's High School Reunion (Seattle 5th Avenue).

Maxx Reed is a multi-genre movement artist and educator, choreographer, director, and multi-medium filmmaker. With the art of movement, theatre, and filmmaking, Maxx aims to show compassion through choreography and creative collaboration—emphasizing his role as a dance educator and multi-platform storyteller.

What (and How) I Learned with Oz Scott

In my role as Columns Editor for SDC Journal, I wroked with director Oz Scott for the What I Learned column, which highlights directors and choreographers sharing lessons learned over the course of their careers. This was published in the Fall 2025 issue of the magazine.

I have carried on the tradition of my father in the entertainment business. He was a preacher—a good one. I joke about it but there is a lot of truth in it. Our jobs are very similar: to make you think, to make you laugh, and to help you to enjoy life. My father was very important to my development as an artist and person. As well as being a preacher, he was a teacher. He taught all the new students that came to Chapel Hill from 1946 to 1959—the imams, priests, rabbis, and ministers. He was an early pioneer in using television cameras for classes. There is a picture in the February 1953 issue of Ebony Magazine of him teaching with one of the big old, bulky cameras.

My style of directing is probably very similar to his. I tell stories when I'm working. For me, telling stories is a way of connecting the actors to who they are, what they should be feeling, and what's going on in the characters' world. Both my father and my mother were inspirations to me. My mother got her master's degree at Teacher's College at Columbia University back in the '50s. She took television/film classes. As a child I remember her talking about cutting film, camera angles, and how long a scene should be.

My mother also took me to see plays. She took me to the closing night of a play on Broadway when I was a kid. It was called A Hand Is on the Gate, a collection of poems and songs that Roscoe Lee Browne had put together to create a Broadway musical. In some ways, it helped contribute to the development of for colored girls, because for colored girls is basically a collection of great poems with a fabulous cast. A Hand Is on the Gate also had a spectacular cast: Cicely Tyson, Moses Gunn, James Earl Jones, Ellen Holly, Gloria Foster, Josephine Premisse, Leon Bibbs, and of course Roscoe. Watching those brilliant actors transform those poems, all of them became friends and inspirations to me. For years, when I'd walk by an old record store I'd look for a copy of Hand Is on the Gate to replace the copy that had worn out. I always thanked Roscoe for that early inspiration.

Another important period in my development as an artist was when I was 19. I was working for a company called Living Stage in Washington, DC, founded by Robert Alexander at Arena Stage. Living Stage was an improvisational theatre company where we went into prisons, halfway houses, daycares, community centers, and schools, performing for kids one day, inmates the next, then a rehab center the next day. I was the stage manager and utility actor when needed. I kept the production going, and gave notes when the director wasn't there. Giving notes for improvisational theatre is different than a play because you're not saying, "This line is wrong. Your blocking was off." My notes were, "I didn't feel it." "I don't know that you made that transition." "Where'd that come from?" "You weren't really in it." That experience very much contributed to who I am as a director today.

We did eight weeks of improvisational theatre rehearsals and then three on the road, six days a week, going from school to school, place to place, prison to prison. So much was inspiring coming out of those performances of Living Stage that we would say, "Every story can have more than one ending." We would get almost to the end and say to the audience, "Okay, how do you want to see this end?" Or, "What else would you like to see?" We'd do two or three different endings. It helped hone my storytelling tremendously because I'm always thinking about what are the other stories? How could it end?

Another significant part of my directing growth came when I took acting classes. I'm not an actor, but I would take acting classes because it made me see, understand, and remember the actor's tools. One time I had this wonderful actor who had one line. It was not a big line, but he couldn't do it. He kept stumbling over it. It's always said that one line is as difficult as 20. So, I went to the side, and I acted it out for him. When I did that, I realized it was a tongue twister. I said, "Oh, it just needs a tweak here. Just a word here, and it'll be great." So I say sometimes: take an acting class. Step outside of your comfort zone.

Oz Scott is an accomplished director of theatre, television, and film. He was integral to the development of Ntozake Shange's for colored girls who have considered suicide/when the rainbow is enuf and directed productions of the play at New Federal Theatre, The Public Theater, and on Broadway. Scott continues to direct regionally and internationally, most recently a production of Intimate Apparel at Arizona Theatre Company.

65 for the 65th

Goal: Celebrate the 65th anniversary of the Stage Directors and Choreographers Society by highlighting 65 directors and choreographers whose work inspired SDC Members and transformed the American theatre. Increase social media engagement and raise the profile of SDC and its Members.

Role: Strategic leadership, project management, graphic design, writing, and research.

Audience: SDC Membership directors and choreographers, industry leaders.

Tactics: Member nomination program including committee leadership, social media campaign on Instagram and Facebook featuring written profiles and Member stories, print publication and distribution to 2,000+ Members and industry leaders.

Impact: Increased Instagram impressions (total times content was viewed) by 346% while maintaining 4-5% engagement rate (industry average 1-3%), with 66% more total engagements (total times people actually took action), Media coverage in Playbill and Broadway World, increased Member engagement, inspiration, and solidarity.

65 for the 65th celebrated the 65th anniversary of the Stage Directors and Choreographers Society by highlighting 65 SDC Members—directors and choreographers who transformed the American theatre—in a year-long social media campaign and print publication.

65 for the 65th included a photo and brief bio of each of the selected artists along with a tribute from another SDC Member, as well as a special “Founder’s Circle” highlighting three SDC Members without whom the Union would not exist. The featured artists were among more than 500 directors and choreographers nominated by SDC’s Membership. The full list of nominees was rigorously considered by a cross-section of SDC Members, with seven rounds of voting before the final honorees were selected.

Social Media Campaign

See it on Instagram

Publication

Read the full publication

Reflections on Zelda Fichandler

Published in SDC Journal, Fall 2024, page 32.

In 1950, a 24-year-old graduate student in the drama department of The George Washington University joined forces with her husband and her professor and converted a former burlesque and movie house into a 247-seat theatre-in-the-round. “I didn’t know what I was doing when the theater opened,” she wrote to a colleague many years later. “I was just going to do plays, and not have them in New York—that’s all.”

The graduate student’s name was Zelda Fichandler, and she would go on to turn that theatre into a renowned cultural space: Washington, DC’s Arena Stage. Zelda (as everyone called her) would serve as Arena’s artistic leader for 40 years, and in the process would become a seminal figure in the American regional theatre movement: an artistic director, writer, director, and leader with a unique ability to recognize and articulate the promise and problems of the field.

Zelda Fichandler and colleagues at Arena Stage in the 1950s. Photo c/o Arena Stage.

Arena’s creation was inspired by another early figure in the American regional theatre movement: Margo Jones, whose nonprofit Theatre ’49 was the inspiration for Arena’s in-the-round configuration. Other theatrical pioneers from that period included the Alley Theatre’s Nina Vance and, after Arena’s founding, Gordon Davidson, Tyrone Guthrie, Joseph Papp, and many more. The theatres that these leaders founded, many of which still exist, now provide the foundation for sustainable artistic careers for a wide variety of American theatre artists: actors, designers, and, of course, directors and choreographers.

When we think about the founders of anything, we tend to think of them as fully formed: complete, successful, with a narrative we know. When someone is much beloved, as Zelda was, that narrative can start to feel perfunctory. You can see it in the repeated language people use to describe someone in this category; they are a “titan,” a “visionary,” a “matriarch.” It’s not that those words aren’t often accurate descriptions. It’s that when we use this kind of clichéd vocabulary to describe someone with an impact as important and varied as Zelda’s, we forget—or lose the opportunity to learn— the qualities that earned them that status, that got them there in the first place: how they were forged, what obstacles they overcame, the specific ways they succeeded and failed, and the values that guided them along the way.

Zelda Fichandler and colleagues at Arena Stage in the 1950s. Photo c/o Arena Stage.

“There are form-givers in every new style of art,” Zelda observed in the last public speech she ever gave, when she was a venerated leader in her eighties, a far cry from her graduate student beginnings. “There may seem to be just one in front,” she told her audience, “but, like seeds under the snow, they emerge in small clusters, and if the plants are strong, they become widely absorbed in the culture.” Zelda, along with her fellow founders, was a form-giver. Those of us who did not know her, or whose theatre careers weren’t directly shaped by her as so many were, nonetheless work in a field that owes its foundation—its nonprofit structure, service organizations, relationship to the commercial sector, artistic leaders, and very way of thinking about our art form—to Zelda Fichandler and her peers. She was the first to admit that she was not the only founder of the American regional theatre movement, but she was for a long time its torchbearer. To many theatre artists, she still is. Her ideas and her accomplishments have become widely absorbed in the culture. They are central to the American theatre as we know it. We could pull out one of those oft-used phrases and say Zelda was a visionary, and it would be true. But it would also be easy— and we learn less from easy.

So it’s a special pleasure that as we celebrate the centennial of Zelda’s birth this fall, we have the opportunity to revisit her life and ideas through two newly published books: Mary B. Robinson’s To Repair the World: Zelda Fichandler and the Transformation of American Theater (Routledge, 2024), an oral history of Zelda’s life and career, and The Long Revolution (Theatre Communications Group, 2024), a collection of Zelda’s writing and speeches edited by Todd London. The books have the same subject but different focuses, and as a result, complement each other well; in fact, it’s hard to imagine a reader who would not benefit from reading both at once.

Robinson’s book is a biography written in oral-history form. It traces Zelda’s life and career through the reflections of her friends and colleagues, interspersed with Robinson’s own writing and excerpts from Zelda’s speeches and letters that give context to others’ memories. London’s book, a collection, has a more straightforward task, although calling it straightforward belies the years of effort it took to bring it to this final form. Zelda began compiling her writing and speeches into a body of work, then bequeathed the project to London at the end of her life.

Readers get a comprehensive sense of what London calls “the range of Zelda’s thinking and the areas of her concern” from The Long Revolution. The collection gives us the opportunity to dig deep into Zelda’s intellectual life and begin to understand her capacity to inspire both through sheer intellectual heft and the clear-eyed focus she brought to the art and artists at the center of the regional theatre movement. A glance at the table of contents indicates the complexity of the project: Zelda wrote, and spoke, extensively, about topics ranging from how theatre is connected to human evolution, to actor training, racial integration, the institutionalization of the American theatre, and more.

It’s in To Repair the World, however, where the unpacking of her personality and vitality happens. “What was it about Zelda,” Robinson wonders in her introduction, “…that caused so many people to feel transformed by her?” Accompanying the author on her journey to answer that question helps us begin to unyoke Zelda from her “visionary” narrative. So do excerpts from Zelda’s letters, which Robinson often quotes in the introductory setups for each chapter in To Repair the World. The letters allow the reader access to Zelda’s doubts and vulnerability, written in a more personal voice than her formal pieces. Of particular note are Zelda’s letters to subscribers, which include a defense of one of Arena’s productions that could be a description of Robinson and London’s mutual pursuit. “To write is to affirm,” Zelda wrote to the subscriber. “Any creative act is a form of affirmation of life.”

SDC and SDC Foundation have their own affirmation of Zelda’s life through the Zelda Fichandler Award, which was established on the occasion of SDC’s 50th anniversary in 2009 to recognize an outstanding director or choreographer who is making a unique and exceptional contribution through their work in regional theatre. For Zelda, the award represented an acknowledgment of a director or choreographer’s accomplishments to date and future promise, created to be given to an artist in the middle of their creative life who has made a long-term commitment to community.

The Long Revolution includes two speeches given on occasions surrounding the award. The first was delivered at SDC’s 50th anniversary celebration in 2009, when the award was announced, and the second at the 2011 award presentation. That later speech, the last Zelda ever gave publicly, is the one in which she spoke about the founders of American theatre as “form-givers.” The 2009 and 2011 speeches are cut and combined in London’s book, but both, especially the 2011 speech, are worth considering separately as capstones to Zelda’s long career. Like much of Zelda’s writing over the years, they contain both celebrations of her own achievements and the growth of the American regional theatre, and warnings about what could hasten its downfall as an art form. In a time of hardship for regional theatres across the United States, it’s helpful to get a taste of both; it’s a chance to learn who laid the foundation and find out it’s not as stable as we thought it was.

And Zelda did lay the foundation. It began, she says in her 2011 award speech, with “a revolution in our perception,” what she, in a June 1959 document published at the end of London’s book, called a “new recognition of the need to establish… permanent repertory theaters” outside of New York. Zelda and her peers wanted to give communities across the United States the chance to experience theatre as an art form, separate from the New York-centric commercialism of Broadway. That left the founders with a problem, however. They needed a different financial structure for their theatres. They landed on the 501(c) (3) tax code, which allowed theatres to join educational, religious, scientific, and charitable organizations in benefiting from “nonprofit” status. The 501(c)(3) tax code hadn’t previously been used for arts and culture organizations, but it would go on to become an essential piece of the American regional theatre.

“Some of us may take that fact for granted, but we shouldn’t,” Zelda stressed in 2011. The nonprofit structure is “the basic reality of our existence.” In fact, Arena started out as a for-profit organization and ran that way for seven years, before W. McNeil Lowry, the Ford Foundation’s director of art and humanities, told Zelda that nonprofit status was a requirement for receiving foundation funding. Arena’s stockholders then voted to turn the for-profit company Arena Enterprises Inc. into a nonprofit. It was one of the first theatres to lead the way into a new nonprofit world.

“Once we made the choice to produce our plays not to recoup an investment, but to recoup some corner of the universe for our understanding and engagement,” Zelda later wrote, “we entered into the same world as the library, the museum, the church, and became, like them, an instrument of civilization.” As Robinson notes, this is a powerful enough quote that Zelda used it repeatedly. In the years since Zelda wrote this, American theatremakers have created thousands of nonprofit theatres. More than 2,000 of them remain a vital part of this country’s cultural life.

Other basic realities of the field that even the most invested and interested theatre artists among us might take for granted— the service organizations that support those regional theatres and the collective bargaining agent that represents them— sprang to life in the 20 years after Zelda and her colleagues started Arena Stage. Theatre Communications Group was founded more than 10 years after Arena, in 1961, expressly for the purpose of connecting the leaders of America’s budding regional theatres to one another. The National Endowment for the Arts began its existence four years later, in 1965. On a parallel track, just a year after that, the League of Resident Theatres was founded as the multi-employer bargaining representative for the resident theatres by a group of leaders including Tom Fichandler, Zelda’s husband, who served as Executive Director of Arena Stage for 36 years. These organizations provided essential support to Arena as it grew and changed, and they continue to bolster nonprofit theatres today. Studying TCG, the NEA, and LORT as part of Arena’s history highlights that these are still relatively young organizations. Their existence, as both Zelda’s story and the NEA’s persistent fight for funding reminds us, is fragile.

While those entities were establishing themselves, Arena found its feet as a successful nonprofit theatre, and the accomplishments Zelda would celebrate in later years began to accrue. The Great White Hope, which Arena produced in 1967 to much acclaim, became the first regional theatre production to transfer to Broadway. The move had far-reaching consequences. Zelda had spent two years developing the play with playwright Howard Sackler, but she received no credit for her work. Arena also suffered. Despite pouring money into the mammoth production, the theatre did not benefit financially from the Broadway transfer. To add insult to injury, it lost its beloved resident acting company and associate producing director Ed Sherin to Broadway.

Motivated by those inequities, Tom Fichlander took action to make sure a situation like this couldn’t happen again. As Molly Smith notes in To Repair the World, the financial implications of the transfer “pushed Tom Fichandler into creating a way for non-profit theatres to enjoy something financial after shows had gone to New York.” This would irrevocably shape the nonprofit theatre sector’s relationship with the commercial sector, sowing the seeds for their current cozy relationship in ways that continue to reverberate today.

Despite its long-term implications, The Great White Hope’s success and transfer were a testament to Arena’s ability to create art with impact. The production played on Broadway for 564 performances, and the play went on to win the 1969 Tony Award for Best Play and the Pulitzer Prize for Drama.

Arena also made an impression on the international stage after it was chosen by the State Department to travel two productions to the Soviet Union as part of a cultural exchange program meant to support the détente from the Cold War. Arena’s productions of Our Town, directed by Alan Schneider, and Inherit the Wind, directed by Zelda, were met with standing ovations in Moscow, to her enduring satisfaction and pride.

As foundations shifted their funding focuses in the late 1960s, the nonprofit theatre sector’s struggle to find alternate funding began, as Zelda saw it, to guide their artistic choices. She diagnosed the problem in a set of 1967 remarks published in The Long Revolution: “What we did—to survive!—what we had to do was to acknowledge that the audience was our Master. What we did was plan a season that would please our Masters—no trick, actually, after so many years of experience.”

Zelda began, in those same remarks, to caution about what is lost when regional theatres focus on the financial potential of their programming choices rather than their artistic merit. “We need money, but as much as we need money we need—individually— to find, heighten, and explore the informing idea of our theatres,” she warned. “Real power resides within the art we make and not in the techniques of manipulation, marketing, and promotion.” Her cautions about this topic would continue to the end of her life.

In her last speech, Zelda returned to her preoccupation with the relationship between nonprofit theatres and the commercial sector. She encouraged artistic leaders to “take our gaze and any preoccupation away, away from Broadway, from which we took our leave many years ago....Broadway must not invade our house and take over our home. Always: he who pays the piper calls the tune.”

Zelda’s impulse to keep nonprofit theatres focused on their artistic impact wasn’t just about mission drift. It was also about theatre artists. Zelda is often spoken about as a great supporter and champion of actors. She believed strongly in a residential company model for regional theatres and worked hard to build and preserve Arena’s. In the second half of her life, she ran the Graduate Acting Program at New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts and so profoundly influenced a generation of American actors— many of whom remain theatre artists—that someone new to Zelda’s story might be forgiven for thinking that her interest in theatre artists was in actors alone. Robinson’s book, however, beautifully emphasizes two potentially less obvious aspects of Zelda’s career: her role as a champion and employer of a generation of directors from around the world, and the way in which her mentorship and her leadership style influenced a generation of American directors.

“As much as we need money we need— individually—to find, heighten, and explore the informing idea of our theatres. Real power resides within the art we make.”

Robinson cites several theatre artists who marvel at the roster of directors Zelda hired at Arena. “They were absolutely world class,” actor Casey Biggs recalls, “Liviu Ciulei, Lucian Pintilie, Doug Wagner, Garland Wright— these incredible directors.” For James C. Nicola, who first came on board at Arena as a directing fellow in a now-defunct NEA program, that was a major attraction of working for Zelda. “The remarkable thing that really drew me to Arena in the first place was the wisdom she had about bringing in directors from other cultural traditions.”

Zelda knew how to let a director have their own space. “When she believed in you as a director, there was another layer of comfort that you knew she would offer. There was always a sense of ‘It’s going to be your production,’” Joe Dowling remembers in Robinson’s book. “The notes she gave were not based on what she would have done with the play, but always based on what she knew I wanted to do with the play.” Dowling, who is Irish, credits Zelda for his success in the United States. “I’ve spent the last 30 years now more in America than in Ireland. That came because of Zel.”

Zelda’s leadership style, in the rehearsal room and in the halls, made an impact as well. “I completely wanted to model my directing style after her,” John Rando says. “The generosity of spirit, the intelligence, the magnanimous way of creating a very safe and playful environment in the rehearsal hall—all those things really added up for me.” Playwright Cheryl L. West thought of Zelda as tough, demanding, and sartorially sharp. “When you see a woman like that, you think perhaps I could do that too. Or I could have my own sense of strength.”

Zelda was a similar influence on, and was a mentor to, many young directors over the course of her career. She often gave them small opportunities and took a chance on them if they did well. Joan Vail Thorne worked as Zelda’s assistant until Zelda hired Thorne to direct in the 1954-1955 season. “It was an act of faith,” Joan remembers in To Repair the World. When Douglas C. Wager was Zelda’s assistant stage manager for An Enemy of the People, she gave him the job of staging the transitions. “That was my first official paid directing job,” he recalls. Wager would go on to a successful directing career and eventually become Zelda’s successor as Arena’s Artistic Director.

Zelda kept an eye on the people she hired and recognized their talents. Sometimes this was life changing. When Ted Pappas was hired to choreograph at Arena, she took him aside. “It’s very interesting watching you work,” she told him, “because you speak to [the performers] as a director, not as a choreographer…you don’t talk to them about steps; you talk to them about why they’re doing it. You’re a director.” Pappas agreed, and went on to a career as a director-choreographer and artistic director.

She also passed on other lessons. What stayed with Nicola “most deeply and profoundly from Zelda was the significance of continuing relationships—artistic collaborative relationships.” Benny Sato Ambush, another mentee, was impressed by Zelda’s artistic identity as “a globalist. I picked that up from her—it started my interest in a universal perspective, in addition to the Black experience.”

As Robinson points out, while Zelda was not always a proactive supporter of female directors (only six women, besides Zelda, directed at Arena in the 35 years she was its artistic leader), she nonetheless had a profound effect on women in the field. Director and writer Emily Mann’s two big influences at the time “were Hallie Flanagan and Zelda Fichandler—[they were] why I felt I could be in the field, I could run a theater, I could write, I could direct.” Irene Lewis felt similarly, she tells Robinson: “Back when I was growing up, you were expected to become a housewife. A theater director was unimaginable.” Zelda, and Nina Vance, changed that for Lewis. “They were the only two women I knew who were directing, and they were only directing because they had their own theaters,” Lewis says.

A director herself, Zelda knew how important it was for her fellow directors to stay in tune with their impulses, particularly if they also took on leadership roles. This is clear in the writing collected in The Long Revolution. “The artist must hear his own voice, at best a highly intricate process. Next to impossible within the cacophony of these institutions of ours,” she wrote in 1970. In the same essay, she cautioned against artistic leaders spending their energy on fundraising and dampening their creative spirit. “The directors, the conductors of the collective creativity, supposedly the fount for the energy and spirit of the Thing, by getting and spending lay waste to their powers,” she warned.

In her 2011 SDC Foundation speech, Zelda reminded her audience that the purpose of regional theatres was, in part, to establish places for artists to work and grow. “We must deepen our commitment to create artistic homes for artists,” so that they “feel that the institution was created for them, to cradle their work, to put them in the center.” Regional theatres, after all, were built both for audiences and for artists. “Where would our writers, directors, and designers be,” Zelda asked, “without these congeries of work places, these sites for experimentation and development?”

We could ask the same question. Where would our community be without Zelda and her many legacies? “American theater has begun to have a tradition,” she wrote in that 1970 essay, “a past, a present, a future, a somewhat coherent way to look at itself and to proceed.” It is to Zelda’s credit that we do have that tradition, for she was a form-giver and an eloquent chronicler along the way.

“Where would our writers, directors, and designers be without these congeries of work places, these sites for experimentation and development?”

It’s helpful to remember that Zelda Fichandler, giant of the American regional theatre, was once a graduate student, a young citizen-artist unsure if she was up to the task in front of her or if what she was making would survive. Perhaps Zelda was thinking of those beginnings when she wrote in her final speech, “The artist may be lonely or feel unsure of, or inadequate to, what she is making, but she must cling to her integrity—her wholeness—and see it through.”

Zelda saw it through. Her enduring belief in the power of theatre to change the world propelled her through a career of constantly shifting cultural headwinds. As she told the NYU acting students in 2001, she believed unequivocally in the “terrible and wonderful power” of theatre’s ability to “reach people’s minds through their hearts and—maybe— change them.” It was so total a belief, so consistently referenced in her writing and speaking, that one wonders where it came from. Recall that line: “I was just going to do plays, and not have them all in New York—that’s all.” Zelda continued, “And then, I found out what a theater could do, in the process of doing it. I found out.” But of course. The artists taught her. The audience taught her. The work taught her. And she continues to teach us.

If Margo Jones struck the match, and Nina Vance lit the torch, then Zelda Fichandler held the flame high for everyone to see. With the way illuminated, others walked behind, their own torches kindled with the flames Zelda passed on. Even as some fires flicker, splutter, or burn out, sparks remain. Some flames burn brightly still, and every day, a young theatre artist lights a new fire. We’ve lost some who led the way, but the message is clear. We must be our own torchbearers now.

Innovations by Kristjan Thor

In my role as Columns Editor for SDC Journal, I edited Kristjan Thor ‘s piece for the Innovations column, which highlights directors and choreographers _________. This was published in the Fall 2024 issue of the magazine.

The word “immersive” often confuses me. It’s hard to define. It’s very buzzy right now and although I hear it being bandied about, I often wonder how many of us have a clear definition of what immersive really means—especially as it relates to theatre, right now. I don’t say that to be mysterious or edgy; I say it because the fact that is it difficult to pin down is exactly the reason I am drawn to it.

My first experience directing something (intentionally) immersive was a modern “horror” adaptation of Maeterlinck’s The Blind in which I put audience members in the hull of a boat on the Hudson, in March, where ice flows scraped the outside of the boat. It was freezing, and we gave audience members parkas and blankets. The actors wore blinding contacts and memorized their blocking by feeling the rivets on the steel floor through their many layers of socks.

After the performance ended, we served the audience a meal consisting of only off-white risottos—all different in flavor but not in look. They were served in communal bowls. Thousands of clean spoons sat at the ready so audience members would take one bite and then retire their spoons, which meant everyone was eating together in a glorious primitive ritual. We drank cheap champagne, and everyone talked about the show—with the actors, with the designers, and most importantly, with each other.

Needless to say, after that experience I was hooked. Directing and producing The Blind (with my longtime creative partner, Josh Randall) became a totem for gauging what excites me, theatrically. The goal became to create affecting events in which the audience’s experience began the moment they pre-ordered the ticket.

At one point, we went so far as to use an automated call/text/email service, the kind that is used by pollsters and consumer reporting services, to send cryptic messages teasing the experience. Direct and bold audience engagement became my new mantra.

Over the last 20 years, I’ve directed plays, feature films, commercials, and events, as well as co-created Blackout, a long-running extreme-fear experience. Many of these gigs have been quite “classical” in their conception: from fourth wall sit-downs to activations at Comic Con. Many less so: from deeply intimate plays in a basement for micro audiences to filling a brownstone with conceptual art and tens of thousands of discarded toy dolls. There is, however, always a desire to give the work a feeling of being all-encompassing, regardless of the genre.

When I study up on the theatremakers of the past hundred years, I immediately see that immersive has long been with us, it just wasn’t articulated as such. One thing that has changed is what working “immersively” means in today’s media landscape. The live experience continues to become more rarefied and scarce as screens and augmented reality move to the front of our daily lives. I don’t bemoan this change; in fact, I see many creators capitalizing on it and doing wonderful things with this new technology.

I do, however, hope that it will make the personal and intimate ability that is inherent in immersive theatre stand out as necessary in the world. Simple and personal gestures will begin to mean so much more in a theatrical experience: sitting alone with an artist intimately whispering their story to me, drifting into the suspended belief that we are the only two people in the world at that moment; being surprised when an actor’s hand is laid gently on my shoulder, both comforted and challenged by its presence; standing in a room that collapses into perfect and total darkness, left only with my thoughts, both terrified and exhilarated.

These are examples of some of the microcosmic moments that have stood out to me as simple, elegant examples of what immersive events can afford our audience. It’s not rocket science, but working with actors and designers to make these experiences present and necessary is what allows the aforementioned moments to stand out.

One thing I’ve come to understand is that performing in an intimate immersive piece requires a whole different set of skills than being on stage. Often actors who have worked with me “experientially” say it can be hard to go back to the stage because the feedback from the audience is not immediate, as it often is in immersive events. Sometimes actors can quite literally feel the audience react. That type of interactivity can be intoxicating.

With AI set to supercharge the output of consumable media, I think these live, human-driven experiences I’ve been describing will become more and more valuable. It is precisely because these types of events are not scalable that they resonate with audiences. Immersive theatre may also be an ideal foil to our relationship to our “personal devices,” ironically, because it is just that: personal.

Kristjan Thor is a critically acclaimed director of film, theatre, and immersive experiences based in New York. Over the course of a 22-year career, he has directed and produced two feature films and many theatre, short film, and video projects that have been recognized internationally.

Theatrical Passports with Arnaldo Galban

In my role as Columns Editor for SDC Journal, I interviewed director Arnaldo Galban for the Theatrical Passports column, which highlights directors and choreographers ______. This was published in the Spring/Summer 2024 issue of the magazine.

In a conversation with SDC Journal, SDC Associate Member Arnaldo Galban spoke about his experience with theatre and directorial style in Cuba, where he was born and began his career as an actor and director, and in the US, where he recently completed a Stage Directors and Choreographers Foundation Observership with director Saheem Ali on his production of Buena Vista Social Club at Atlantic Theater Company. Buena Vista Social Club dramatizes the making of the beloved Cuban album of the same name, following the stories of a group of veteran musicians as they record the classic songs. The show was Galban’s first experience with professional theatre in the United States.

What is the theatre scene like in Cuba?

In Cuba, we have so many talented artists but all the cultural institutions, all the venues, belong to the government, which means they’re paying your salary and they’re producing your plays. They can attend performances before opening night, watch what you’re doing, and decide if you’re opening or not.

Independent theatre is illegal in Cuba, because that means you’re doing theatre with your money, so the government can’t censor it. You can’t do theatre outside the institutions, and you can’t sell tickets. The government won’t say, “Oh, we don’t allow independent arts in Cuba,” but they will make sure that you can’t make independent theatre.

I had friends doing that work. They were put in jail, or they were threatened. It’s a very difficult environment if you want to be a free thinker and create something. Which is crazy, because the Cuban Revolution has invested so much money in cultural things in Cuba. You can go to a cinema for a few cents, or you can buy a book and it’s less than a dollar. Everything that’s cultural in Cuba is so affordable. They’re giving culture to the people, and at the same time asking you not to use your brain, which is so confusing.

As a young artist, you’re very confused, but also it gives you that kind of rebel spirit that says, “Oh, you don’t want me to do that? Now I’m going to do that, and I don’t care if I’m not making money.” It’s beautiful; you do it because you really want to do it, because you love it.

What was your directing experience like there?

I was directing, I was designing, I was building the lights. I learned that from one of my favorite teachers and theatre directors in Cuba, Nelda Castillo. She made everything in the theatre with her hands. I learned that from her. I built lights with tomato cans. I built whole electricity systems. It was an adventure.

What was your concept of a director then?

In Cuba, we don’t have a place where you can study directing. You can study as a playwright, a designer, an actor, a critic, but not a director. Almost all the directors I worked with in Cuba learned to direct by trial and error while they were actors in a very important company called Teatro Buendía and the director there supervised their processes.

Those directors inherited skills from her, but they also inherited her style. In Cuba, the director has the last word on everything. They tell people what to do all the time. That happens everywhere in Cuba: in your house with your dad, in all different kinds of work environments. But in theatre, they use a very tyrannical style. That’s the way I grew up, seeing these directors call actors names or humiliate them in front of the rest of the company. I think we inherited that because of politics in Cuba. Our authority model is, “If you are not with me, you’re against me. You’re the enemy.”

I learned a lot from the directors I worked with there, and I will always be grateful for that. But I think in Cuba, no one realizes we’re following a model or a style that is against creativity. Especially with theatre; it’s such a communal art. And I think that’s what I saw here with Saheem Ali on Buena Vista Social Club. In America, you are in a creative process, and you are co-creating with all these people that are part of the creative team.

How was Saheem’s style of directing different from your previous experience watching directors work?

Well, first of all, Saheem is so kind. He learned my name. He said hi to everyone. He took time to acknowledge that we were present in the room. He even took time to unite the company and have everyone introduce themselves, and ask, “How did you arrive here?” and “What is your connection with the material?” I saw people hopping up and sharing deep and emotional stuff, because he was able to create this environment that made people feel safe to share.

That’s him, that’s who he is as a person. The people he feels comfortable working with are also people with this style. They are very human, and humble.

Saheem also considered other people’s ideas. If he was talking about something, and he had an idea, and then someone suddenly realized, “Oh, there is this way of doing this,” he was able to say, “Oh, yes, let’s try that.” My previous experience with other directors was that they respond to other people’s ideas with, “Oh, I didn’t have that idea. I know it’s amazing, but I won’t say that, because that means you are more creative than me, and I can’t put my work at risk.” Saheem was able to be open and say, “Let’s try that,” and the show got richer and richer.

Does that style inform how you think about making work now?

The way I will approach the next thing will be different thanks to the experience I had with Saheem. I would love to imitate his style of inclusive directing, listening to everyone, being humble, that kind of thing.

I feel lucky to meet people who are showing me there’s a different way to be a star and a different way of being a talented director, and that doesn’t mean you feel you are above everyone.

Arnaldo Galban is a director, actor, and acting coach based in New York City.

Theatrical Passports with Garry Hynes

In my role as Columns Editor for SDC Journal, I interviewed director Garry Hynes for the Theatrical Passports column, which highlights directors and choreographers ______. This was published in the Winter 2024 issue of the magazine.

Druid Theatre’s DruidO’Casey project included three Sean O’Casey plays—The Plough and the Stars, The Shadow of a Gunman, and Juno and the Paycock—in marathon performances in New York City and Michigan in fall 2023. The plays, commonly known as the Dublin Trilogy, were originally written separately and staged individually in the 1920s at Dublin’s Abbey Theatre. Garry Hynes, Druid Theatre’s Co-Founder and Artistic Director and the director of DruidO’Casey, chose to stage them chronologically, in order of the dramatic events depicted—which span 1915–1922 and encompass Ireland’s Easter Rising, War of Independence, and Civil War—rather than in the sequence that they were written. While audiences were able to see individual plays on separate nights, the project was conceived and designed as one marathon production, to be experienced as one play in three parts.

While O’Casey’s plays, now considered Irish classics, are often treated naturalistically, Druid’s production design leaned into the theatricality of both the marathon event and O’Casey’s language and sensibility. Hynes’s direction highlighted moments that felt heightened, performative, and sometimes surreal.

What did the decision to stage the plays in chronological order teach you about them?

I’ve done two O’Casey productions in my career before this, and one of the things that’s always worried me a bit about the plays is that unless one does a very modern production or a production totally removed from O’Casey’s ground plans or the period, then you’re forced back into this world of the Georgian tenement or the Georgian House. Knowledge of it has slipped away with time and as a result, the signaling has gone very wrong, because living in a distressed Georgian room would now be only the recourse of the wealthy. I think that because we were doing the three plays together, I felt able to take the decision to set them in a world that didn’t have to go for those set of references because we had a better chance of creating our own world.

A number of things became clear as we really got into rehearsals. Because the plays—to our knowledge, and as much as we could research—have never been seen together, one after the other, they tend to be swapped out one for the other, or certainly Juno and Plough do. And it became very clear as we worked on them how detailed O’Casey’s use of the historic detail of the time was, to distinguish each play. The detail of the historic events fed into the domestic events in a way that I just was in awe of: the craftsmanship of that. A suspicion that I had—that the plays were first, haunted plays, and second of all, plays that haunted each other—very much affected me in the making of it.

How did you and your design team approach the monumental task of designing three separate plays into one marathon production?

I knew that we were going to more or less follow O’Casey’s ground plan, and I knew we were going to use the profile of the costumes. So then it became really a question of what material to use, what was the nature of the room?

O’Casey is often called naturalistic, but more and more, I don’t find that word useful to describe his work. His work is so performative, so it started to make sense to consciously acknowledge its performativeness by using flats, stage weights, and those kinds of references.

The use of color in the costume pieces (by set and costume designer Francis O’Connor and co-costume designer Clíodhna Hallissey) was striking.

We knew that we weren’t going to go for documentary realism, and I talked a lot about the need to be able to completely embrace the performative aspects: the music hall, the broad comedy, the ability to go from tragedy one second—I mean, [the character of] Bessie Burgess [in Plough], also our Juno, has to die at the end of the play—but I didn’t want that to stop us from absolutely bringing the characters to vivid life. Some of that thinking influenced us to go for a color range that would not necessarily have been available at that time. Say something like Nora’s yellow dress [in Plough]. It’s stunning. She would not have worn something like that. But that’s part of the conscious sense of “this is going to be as theatrical as we think O’Casey was in creating these plays.”

O’Casey wrote such beautiful female characters, who you clearly also have such respect for.

When I think of it, all I can think of is O’Casey’s dedication, I think it’s in Plough, to his mother, where he says, “To the gay laugh of my mother at the gate of the grave.” which I think is rather beautiful and wonderful and sums it up... It’s a wonderful celebration.

I think some of his celebration of women comes from the fact that—I don’t know if he ever said it—but that he was so aware of the awfulness of individuals’ lives and that in some way the women, while they worked incredibly hard and were so poor and so on, they still had a central place in life as mothers of their children, as rearers of a family. Whereas the men, as victims of the capitalist economy, really had so little of anything to give them dignity or a sense of purpose. Somehow I tend to feel that O’Casey felt that too.

How do you think O’Casey’s legacy reverberates in modern Irish literature and theatre? Are there playwrights that you feel are working in O’Casey’s vein?

Let’s put it like this, I don’t think they are, unless they’ve been influenced by O’Casey. Writers who write about Dublin or write urban plays and/or use a Dublin accent can easily be referenced to O’Casey. But what O’Casey does—and working on the plays like this made feel this even more—his influences were extraordinary. He was very much influenced by the music hall. He was influenced by the Irish theatre that he saw, and then the use of music, the use of language—obviously J.M. Synge would’ve been an influence of some kind. Then there was his work at the Abbey Theatre and whatever sort of influence that was to work with those actors on a consistent basis. I just think what he came up with, which has become—people use the word “O’Casey-like” or whatever, which can seem very hackneyed—I think he was extraordinary, extraordinary as a writer.

Garry Hynes is the Co-Founder and Artistic Director of Druid Theatre in Ireland and was previously Artistic Director of the Abbey Theatre, Ireland’s national theatre. In 1998, she became the first woman to win the Tony Award for Best Direction of a Play, for Martin McDonagh’s The Beauty Queen of Leenane.

FloodHelpNY Out Of Home Advertising

This OOH advertising campaign was designed for FloodHelpNY, a project of The Center for NYC Neighborhoods, and displayed on buses, New York City ferries, the Staten Island Ferry, and in ferry stations in NYC during hurricane season in 2023.

Goal: Educate NYC homeowners about flood insurance during hurricane season.

Role: Campaign lead. Led end-to-end development and execution of a hurricane season flood insurance awareness campaign, including creative concept, copywriting and graphic design, stakeholder management with grant funders, strategic placement planning, vendor coordination, and project and budget management.

Audience: NYC homeowners at risk for flooding.

Tactics: Deployed advertising placements across NYC bus routes, ferry networks and stations to capture audiences during their daily commutes, timing the campaign during hurricane season when flood risk awareness was most relevant and actionable.

Impact: Delivered critical insurance education to thousands of daily bus and ferry passengers across multiple boroughs, ensuring homeowners encountered potentially life-saving financial protection information precisely when seasonal flood risks were elevated and policy decisions most urgent. Bus ads recieved approximately 34,940,021 impressions over 3 months.

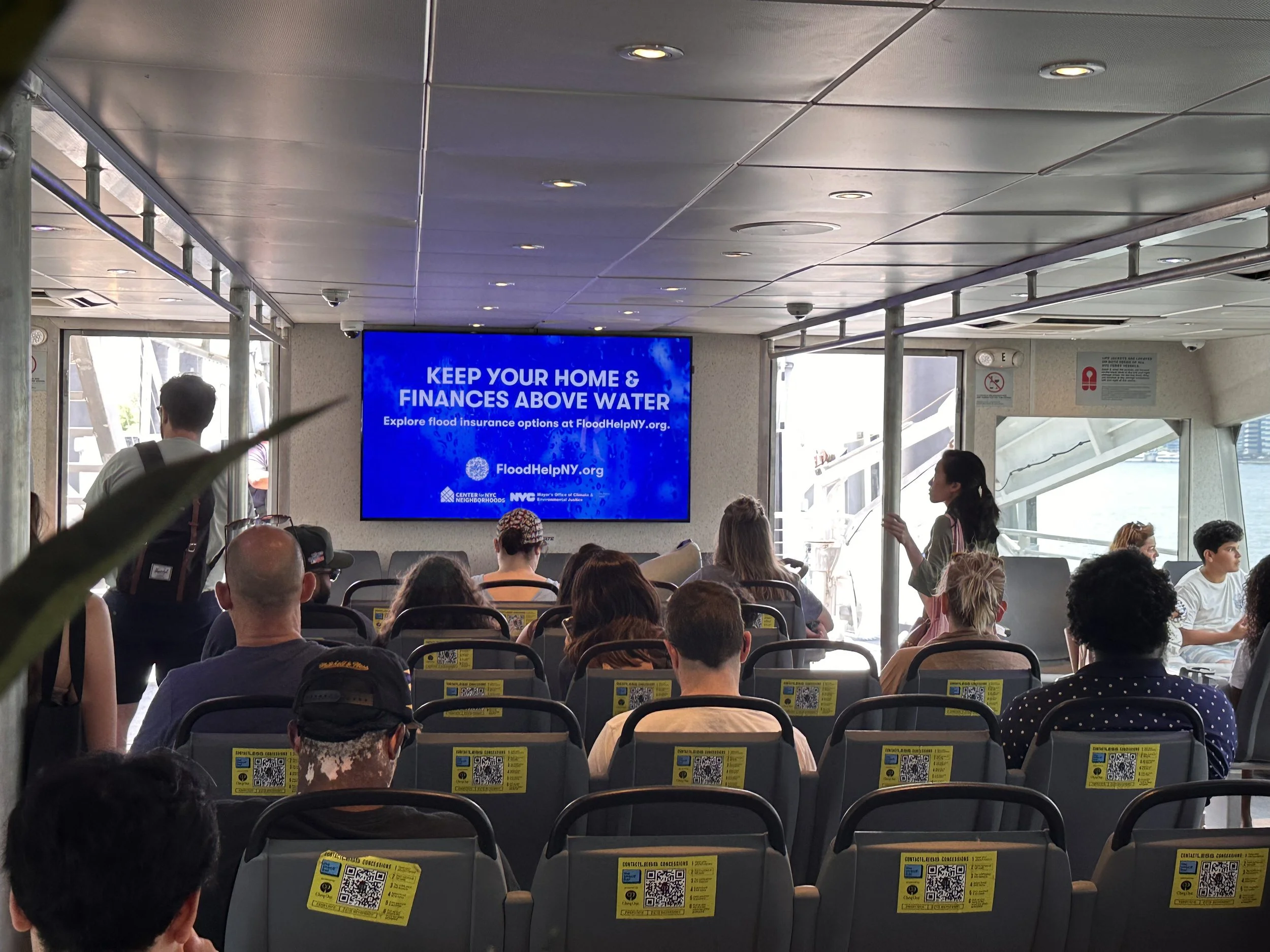

Ferry Ads

Ferry ads were placed on both the NYC ferry system and the Staten Island Ferry system, which required working with two different vendors in both shipboard posters, wall murals, and digital ads. The ads ran from July through September 2023, in hurricane season.

NYC Ferry Ads Vendor: Interstate Outdoor Advertising

Staten Island Ferry Ads Vendor: Island Adworx

Station Zippertron Ads

Zippertron Ads were displayed in the Manhattan/Whitehall ferry terminal to capture impressions during high-traffic moments when passengers were waiting for public transportation.

Vendor: Island Adworx

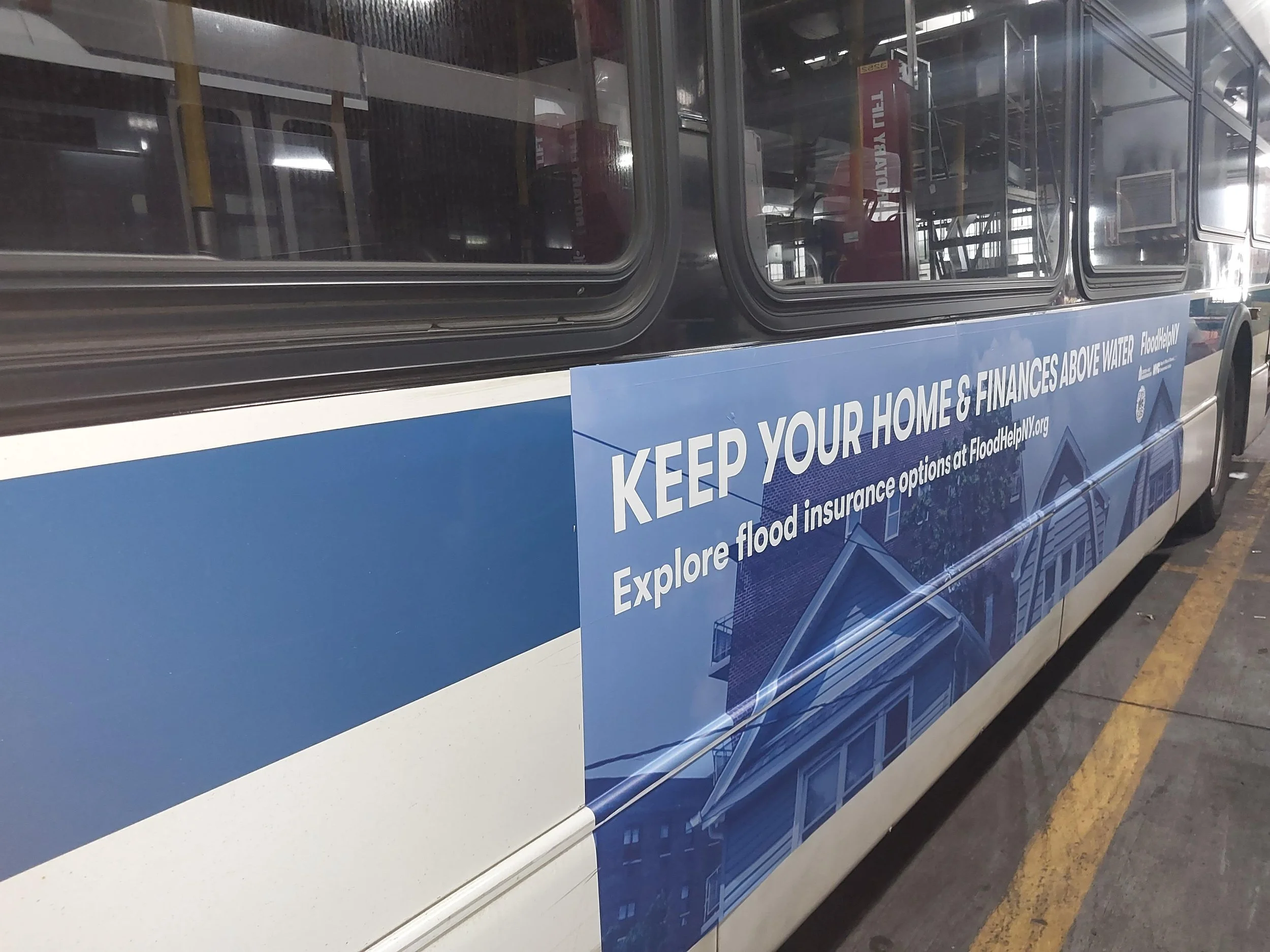

Bus Ads

Bus Ads were placed on routes targeted by their proximity to neighborhoods at particular risk for stormwater flooding. The ads ran for three months, from July through October, 2023.

Vendor: BillUps

Impressions: Approximately 34,940,021 over 3 months.

FloodHelpNY is funded through the New York Governor’s Office of Storm Recovery and New York Rising and FEMA through the Mayor’s Office of Climate and Environmental Justice/Housing Preservation Development.

New Flood Legislation Will Require NY Landlords to Disclose Flood Risk to Renters

Originally published on FloodHelpNY.

Goal: Raise awareness of a new law requiring landlords in New York State to disclose flood risk, prior floor history, and available flood insurance to tenants.

Role: Writer

Audience: NYC homeowners and renters.

Starting on June 21st, landlords in New York State will have to disclose flood risk and prior flood history to tenants in their leases and provide a notice of available flood insurance. Senator Brad Hoylman and Assembly Member Robert Carroll sponsored the bill, which Gov. Kathy Hochul signed into law in December 2022.

“As flooding becomes more frequent and intense due to climate change we must make sure New Yorkers have the information they need so that they can protect their property and their families,” said Assembly Member Carroll in a statement. “New York State has lagged behind other states when it comes to flood risk foreclosure for tenants and this legislation is an important step forward.”

The new law launches at a timely occasion because June is the start of hurricane season and New York has been battered by storms in recent years. In 2021, Hurricane Ida killed 17 people in New York State, primarily in low-income, immigrant communities in Queens. This intersection of affordability and climate change vulnerability continues to be a prominent thread in New York’s housing narrative, with limited lifelines. One option for residents to protect themselves and their finances in the event of a flood is purchasing flood insurance.

“From now on ALL renters across New York State will be more informed about flood risks, flood insurance, and what it means to live in a highly floodable area or floodplain at the time of signing a lease,” Waterfront Alliance President and CEO, Cortney Koenig Worrall said at the time the bill was signed into law. “Hurricane Ida was the most clear indication of the extreme risks to rental units and the need for solutions.”

New York renters are not the only ones who have been going into housing agreements without flood knowledge. Homebuyers also have flimsy protection. As of right now, sellers can pay a paltry $500 fine and avoid disclosing flood damage to buyers. This puts homebuyers in a precarious situation that could lead to significant financial losses throughout the life of the mortgage if flooding occurs. Future fatalities, displacements, and dollars spent on damages could be reduced in the future with appropriate laws and policies enforced now. The only way to ensure financial protection from flooding is to explore and purchase flood insurance options.

If you are signing a new lease on June 21, 2023 or later, take the time to read through the lease and make sure flood risk and prior flood history are included. Your landlord is also obligated to inform you of flood insurance availability. Flood insurance can help protect your home and your financial interests. Landlords, the time is now to gather the necessary facts, flood insurance options, and accordingly modify leases and tenant informational materials.

BREAKING NEWS: We’re excited to announced that on Friday June 9th, NYS passed disclosure laws to give the same protections to buyers and removes the $500 loophole. Now it’s onto the Governor for signatures.

Diversify NYC’s Housing Stock

I edited this blog post by Yvette Chen, Program Manager for The Center for NYC Neighborhoods, in April 2023.

Goal: Raise awareness of alternative housing models in NYC.

Role: Editor. I collaborated with Yvette and the program management team to specify the focus of the blog and ensure the writing was accessible and focused on our audience and the piece was designed for Medium’s blog format, and I worked with Yvette to choose relevant images that kept the audience’s attention.

Audience: NYC policy-makers and homeowners looking for alternative solutions to the NYC housing crisis.

The Problem: Black Homeowners Are Leaving NYC

As costs of living, and owning a home, continue to rise, Black homeowners are struggling to stay in New York City. We see it over and over again in news coverage, and from Black homeowners who reach out to the Center for NYC Neighborhoods looking for guidance as they fight to keep their homes.

We see evidence of this frequently, in the stories of homeowners who call our Homeowner Hub. There is a homeowner from the Bronx, who lost her income and fell behind on her mortgage payments struggling to keep her home. Another homeowner in Queens wants to pass her home on to her loved ones in the future but doesn’t know how to do so. Then there’s a homeowner in Kings County, whose loss of income caused her to fall behind on her water bills and the home repairs she needs. The specific issues vary, but the underlying challenge is the same — New York City homeowners are struggling, and we need solutions.

Solution: Alternative Housing Models

Many existing approaches to the housing crisis do not address the growing trends in the decline of homeownership and the loss of permanent affordable housing in communities of color. One solution: alternative housing models that specifically aim to combat racial disparities in affordable homeownership, including community-controlled purchase policies, community land trusts (CLTs), and limited equity co-ops. These approaches preserve existing housing, create permanent affordability, and remove housing from the speculative market. These shared equity housing models also foster community, long-term affordability, and the opportunity to build generational wealth for communities that have been shut out for too long.

Solution: Community-Controlled Purchase Policies

Tenant and Community Controlled Opportunity to Purchase policies map, PolicyLink

Tenant and community opportunity to purchase policies are an emerging anti-displacement strategy that lock in affordability and offer an entry into homeownership opportunities to current residents. TOPA, or the Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act, gives tenants in most residential buildings the first offer and first right of refusal if their landlord decides to sell the building. TOPA was first enacted in Washington, DC in 1980 and since 2002, has preserved over 3,500 homes in the city.

COPA, the Community Opportunity to Purchase Act, complements TOPA by requiring owners of buildings to notify qualified non-profit organizations before listing the property. These organizations have the right of first offer and refusal. TOPA and COPA are gaining traction in areas with highly speculative markets, such as New York City and the Bay Area, because they create a meaningful opportunity to slow down the speed of real estate transactions so that communities can consider their options, and counter neighborhood change and the high costs that can come with gentrification.

Solution: Community Land Trusts

Community Land Trust Directory, from the Center for New Economics

Community Land Trusts (CLTs) are another important piece of the puzzle in buttressing affordability and removing land from the speculative market. In the CLT model, land is owned in common by a CLT, a nonprofit chartered to hold the land in perpetuity. The CLT model is also less risky than the traditional housing market; a study found that during the Great Recession, 82% of seriously delinquent homeowners were able to avoid foreclosure with assistance from the CLT. The CLT movement, which originated from the Black Civil Rights movement, is now one option that, together with the other alternative housing models listed here, can help make homeownership sustainable for Black families.

Solution: Limited Equity Co-ops

Co-op City, NY Daily News

Co-ops are another example of a shared-equity model of homeownership. Co-op residents buy shares in a co-owned building, known as an “equity deposit.” These shares can be sold at either market rate or below market rate in limited-equity co-ops. Currently, co-ops comprise nearly 75% of Manhattan’s apartment stock.

What’s Next for NYC & Alternative Housing Models

NYC has a history of successful use of alternative models, and there’s a lot we can build on. Currently, there are 17 CLTs throughout New York City, including Interboro Community Land Trust, which is one of the Center’s most important partners. Interboro CLT is the only New York City based CLT to focus on permanently affordable homeownership, and their pipeline includes homeownership projects — limited-equity co-ops (LECs) and single-family homes — in Brooklyn, Queens, and The Bronx. Community land trusts like Interboro can benefit those who would otherwise not have the opportunity to become homeowners and help homes maintain their affordability in areas of the city that are rapidly gentrifying.

The Mitchell-Lama program, introduced in 1955, created affordable co-op housing for low- and middle-income households, While nearly 20,000 of the original co-ops have been converted to market rate since 1989, some examples, like Co-op City, still offer long-term affordability to residents.

In order to successfully and meaningfully address housing needs of NYC’s Black community , we need new funding and capacity building mechanisms to support bold structural change in the housing market. Pairing alternative housing models like the ones above with existing popular solutions, like inclusionary zoning, can help NYC produce solutions in homeownership. These alternative models — shared equity models of housing, paired with policies like TOPA/COPA — not only help create permanent affordable housing opportunities, but also further a collective vision that honors our city’s need for housing justice.

Yvette Chen is a program manager for the Center for New York City Neighborhoods.

Blog: What The Homeowner Hub Learned about New York Homeowner Needs in 2022

Originally published on The Center for NYC Neighborhoods blog.

Goal: Raise awareness of the unique work of the Homeowner Hub by highlighting individual stories of homeowner’s helped by their work and summarizing the work and changes in the homeownership ecosystem in 2022.

Role: Writer

Audience: NYC homeowners, grantee partners, policymakers.

A senior citizen on disability who had twice been a victim of deed theft. A first-generation immigrant in South Brooklyn facing foreclosure on their family-home after falling behind on his mortgage payments. A group of tenants on a rent strike after realizing that their original landlord was a victim of deed theft and they were paying rent money to a scammer.

These are just some of the homeowner stories that our Homeowner Hub encountered in 2022 as they worked to assist homeowners across New York State.

The Homeowner Hub, a dynamic, multimedia, knowledge and referral center, is staffed by a team of homeowner service experts whose knowledge of the needs of New York City homeowners make them effective and compassionate front-line staff. The Hub triages homeowner issues, makes top-quality referrals, and provides case management services — with expertise in handling difficult conversations and a focus on providing a superior homeowner experience. It offers bilingual access for homeowners via webforms and chat functionality.